Measuring Income Inequality in Israel – a Historical Perspective

State of Research

Research concerning income inequality in Israel has some basic data problems to solve to achieve reliable results. This issue is due to the historical conditions (such as the frequent conflict) and political decisions of the state (concerning the deficiency of lingering and stable data-collecting policies). Although in one important article on this topic, “Origins of Income Inequality In Israel: Trend and Policy (2005)”, Ofer Cornfeld and Oren Danieli strive to provide, for as long a period as possible, a solution to this issue, they only exhibit a proper demonstration for the later period of Israel, and they do not pay enough attention to the reliability of data. In terms of historical series, the issue of income inequality in Israel remains an open question.

Possibilities and Problems of Obtaining Data

In many aspects, Israel has a special position regarding income inequality. According to the IMF (2020), Israel has an advanced economy; and according to the United Nation Development Program (UNDP, 2019, p.304), it has a very high HDI; however, according to the WID (2020), it is the only developed country that cannot provide data about economic inequality. Three problems stand out regarding explaining this data-providing issue, each on a different level. The first problem concerns describing the field of data due to political and legal uncertainties (especially in terms of the legal borders of the state); the second problem concerns the representativeness of data due to the huge ethnic and social diversity in the country (specifically the extreme gap between the different groups in terms of their economic conditions); and the third problem concerns the deficiency of a long-term policy to collect data due to the frequently changing administrative structure.

First Problem: Political and Legal Uncertainties

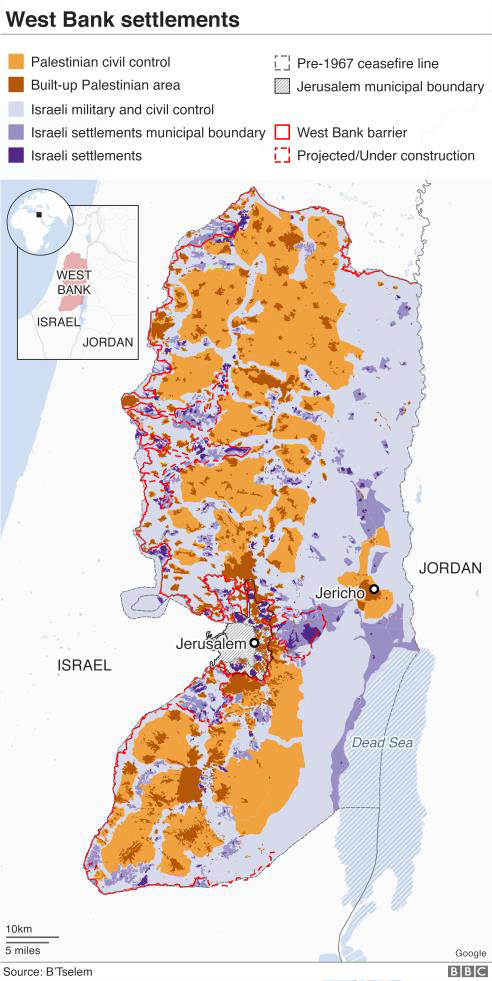

The official foundation of the state of Israel is based on a UN agreement that defined the administrative structures and political borders of the Israel and Palestine region. However, this agreement was very short lived, and today the prevailing edifice and legal borders of the region are, in most cases, unclear. This problem is significant because the legal border discussion includes heavily populated areas; while Israel claims as de facto thousands of Palestinians as part of its population (even the number of people is unclear), these people belong as de jure to Palestine. The vagueness concerning the border (which also is related to the state's official population) makes it, undoubtedly, difficult to interpret any statistical data due to the uncertainty regarding "official" citizens.

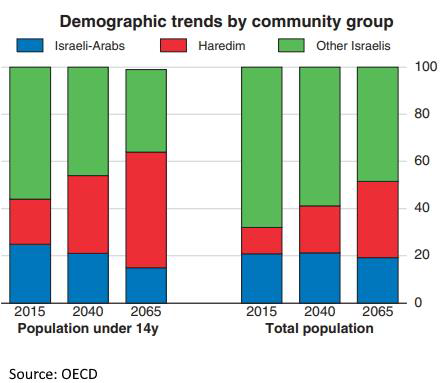

Second Problem: Social and Ethnic Diversities

Israel has a unique multicultural, multireligious, and multiethnic status. In some cases, diverse groups live more homogenously and in similar conditions; in other instances, some groups have strictly isolated and autonomous characteristics. Most important, however, is the huge gap between the three main groups that comprise most of Israel’s population (Israeli-Arabs, Haderim, and Israelis) regarding the economic conditions, which makes the representativeness of general data problematic. For instance, while there are no constant data concerning wealth accumulation in these groups, “[t]he wage gaps between the Jewish and Arab populations in Israel are large” (Cornfeld and Danieli, 2005, p. 75), and there are not enough reliable data about the Haredim because they follow a radically isolated communal life.

Third Problem: Administrative Policies

Israel has had many administrative troubles due to the long-term war conditions, which created several obstacles for a lingering and constant administrative policy. In this respect, there are some deficiencies and disconnections in terms of perennial data collection strategies, which are crucial for generating historical series regarding income inequality. For example, the West Bank settlements' administrative structure is unclear due to the enormous difference between the de facto declaration of Israel and the de jure status of the land.

Striving to Measure Inequality in Israel

Despite all these structural and historical problems regarding collecting data in Israel, there is a historical Gini index, provided by the World Bank in the context World Development Indicators. In many aspects, the index is one of the most overarching series regarding economic inequality, comprising an almost 40-year period.

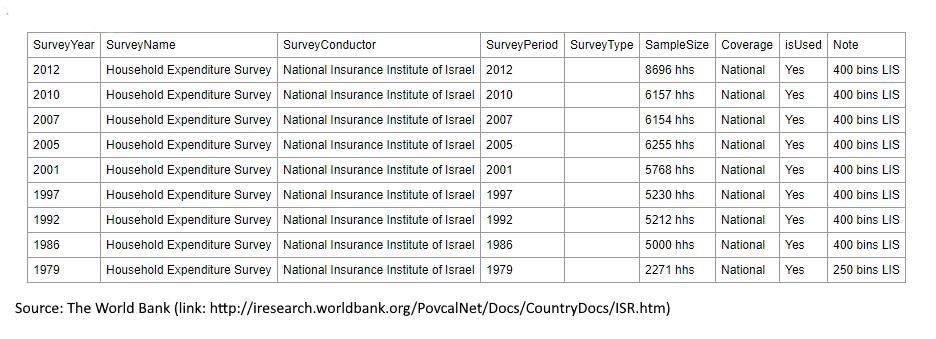

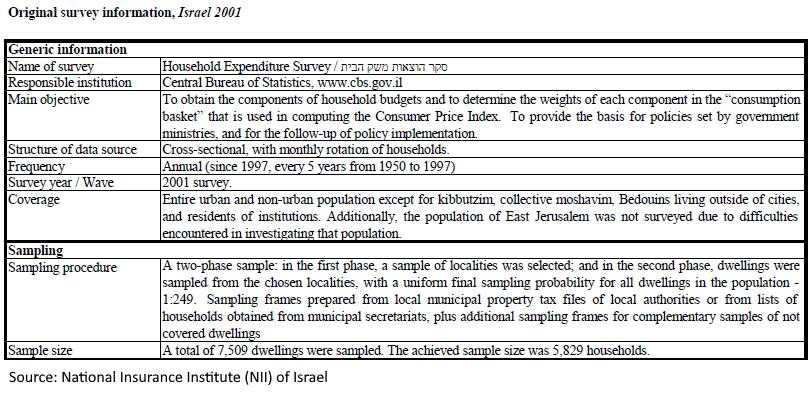

However, many projects and databases concerning economic inequality still prefer not to use these data in their comparisons. Two points stand out regarding this choice. First, the absence of data about wealth inequality makes it almost impossible to understand general economic inequality in Israel only by referencing income inequality. Therefore, projects that try to demonstrate general economic inequality in different countries cannot exploit these data properly, and so prefer to not use it. Second, there is some suspicion regarding the reliability of data – for instance, Cornfeld and Danieli (2005, p.59) used the historical Gini index only after 1997 – due to the data collection method. The only World Bank source for this index comes from the Household Expenditure Survey, which was conducted by the National Insurance Institute of Israel.

While the Bureau of Statistic Israel was mainly responsible for surveys related to taxation and future policies (especially regarding defining the infrastructure problems that need the state‘s investment), it has never investigated income and wealth sharing. The reason for this lack is partly the absence of estate or wealth tax in Israeli tax policies, and partly due to public discourse regarding the tax duty, which describes income tax as a civil duty for citizens without state control (Likhovski, 2017, p. 282). On the other hand, the National Insurance Institute of Israel was responsible for defining income sharing for the mandatory health insurance contribution, which led to them collecting data. The main data source for the Gini index comes from the National Insurance Institute of Israel thanks to their administrative obligation. However, the problem is that this institution had no experience in collecting data and failed to apply a perennial and stable data collection method.

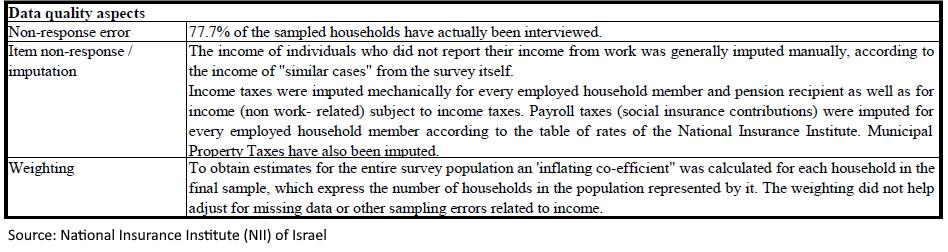

From this standpoint, historically, there were many problems concerning the data-collecting methodology. These problems are evident in the survey itself. However, the first problem is that there is no information about the first two surveys (1979 and 1988); therefore, the structure of the data source is not clear, nor are the coverage and sample procedures. Nevertheless, especially given that there is almost perfect stability in the Gini index between 1979 and 1988, the reason could be the huge reduction that was abstractly inferred from the lack of data. The second problem is that there are inconsistencies between the surveys until 2000. For instance, in the 1992 survey, urban localities with fewer than 2000 inhabitants and rural localities were excluded, which was crucial given that it is predominantly the Arab population who lives in these categories. This exclusion makes the representativeness of the data problematic.

Furthermore, only 77.7% of the sampled households were interviewed.

The 1997 survey followed an entirely different sampling procedure, which makes it impossible to apply strict definitions about the framework, since only municipal tax files were analyzed, and the tax collection procedure, especially in the West Bank settlements, is unknown due to the illegal status of this land.

The 2001 survey contains a detailed description about choosing the sample, but many social groups and East Jerusalem were outside the framework.

Therefore, it is not clear whether the stable increase in the Gini index between 1990 and 2005 is the result of a historical change or just a result of the methodological adjustments.

After the 2005 survey, the same coverage and sampling procedures have regularly been applied, meaning they are more comprehensive than previous surveys; however, problems remain regarding the representation of all social groups.

Since communal groups such as kibbutzim and moshavim, and some traditional nomads such as Bedouin, live mostly outside the main centers, they have very diverse and unclear economic conditions due to their unique lifestyles.

Although it is plausible to conclude that the changes in the Gini index from 2005 to 2016 were probably the result of some historical thriving rather than methodological adjustments, the problem of the representativeness of data remains due to the exclusion of various isolated and autonomous groups that have different economic conditions.

Overall, while the Gini index of the World Bank is the only comprehensive historical data regarding economic inequality in Israel, it has three problematic characteristics: first, the period between 1979 and 1988 is entirely unreliable due to the absence of the surveys; second, it seems highly unlikely that the differences in the index between 1990 and 2005 was caused by historical change rather than methodological inconsistencies; third, although the changes in the period from 2005 to 2016 seem to be the result of historical developments, the representativeness of this period remains problematic regarding generalizing this change to all Israel.

Therefore, measuring economic inequality in Israel, in many aspects, is an ongoing research project, and there are many questions due to the historical, political, and social features of the country. Although there are some incomplete indicators, for example, Cornfeld and Danieli (2005, p.60) using a Gini index for hourly wage inequality between 1987 and 2011, derived from data provided by the Income Survey of the Central Bureau of Statistics, there are no available example surveys, meaning reliability is unknown. Therefore, different interpretations regarding economic inequality are possible. The deficiency of constant and overarching data is one of the main challenges regarding achieving accurate results.

References

- Cornfeld, Ofer & Danieli, Oren 2015, ‘The Origins of Income Inequality in Israel: Trend and Policy’, Israel Economic Review, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 51-95.

- IMF 2020, World Economic and Financial Surveys(link:https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2020/01/weodata/groups.htm; access in 20.10.2020)

- International Labour Organization 2018, The Occupied Palestinian Territory: An Employment Diagnostic Study, Beirut.

- Likhovski, Asaf 2017, Tax Law and Social Norms in Mandatory Palestine and Israel, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- National Insurance Institute (NII) of Israel, Original survey information, Israel 1992.

- National Insurance Institute (NII) of Israel, Original survey information, Israel 1997.

- National Insurance Institute (NII) of Israel, Original survey information, Israel 2001.

- National Insurance Institute (NII) of Israel, Original survey information, Israel 2005. OECD 2018, Economic Surveys: Israel.

- United Nation Development Program 2019, Human Development Report, New York World Bank 2020.

- World Bank National Accounts Data. World Inequality Database https://wid.world/world#sptinc_pp9p100_z/WO/last/eu/k/p/yearly/s/false/15.30549999999999/22.5/curve/false/country ; accessed on 20.10.2020

Kerem Duyums

MA History Student